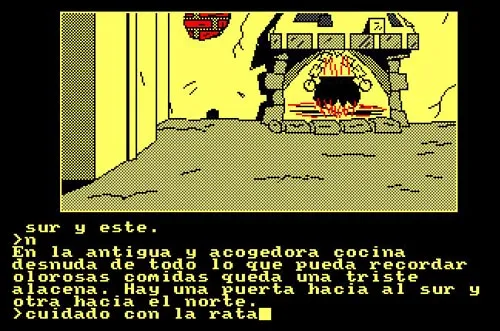

There is a game from my youth on which I spent countless hours as a small child with my Amstrad CPC 6128. I have very fond memories of spending the full afternoon trying to move around in its map. If you are thinking it is a super advanced 3D game with fast paced action you are absolutely wrong.

The game is Don Quijote. A text based adventure.

Yes. Just some super naive graphics. A small REPL-like interface and you are good to go to live amazing adventures.

Since we are in the world of AI one tiny fun experiment I fantasized about is letting the AI play the game on its own to see how far it could go.

Even if I loved that one it is not the optimal choice to use as a learning point. I want something with better feedback on the status of the game.

There is one oldie but goldie I can use for that.

Well, I can use many games in reality but is a good one because it has a score. In the game you have to get some items, place them in the shelves and you get points for that.

Experiment 1: The naive start

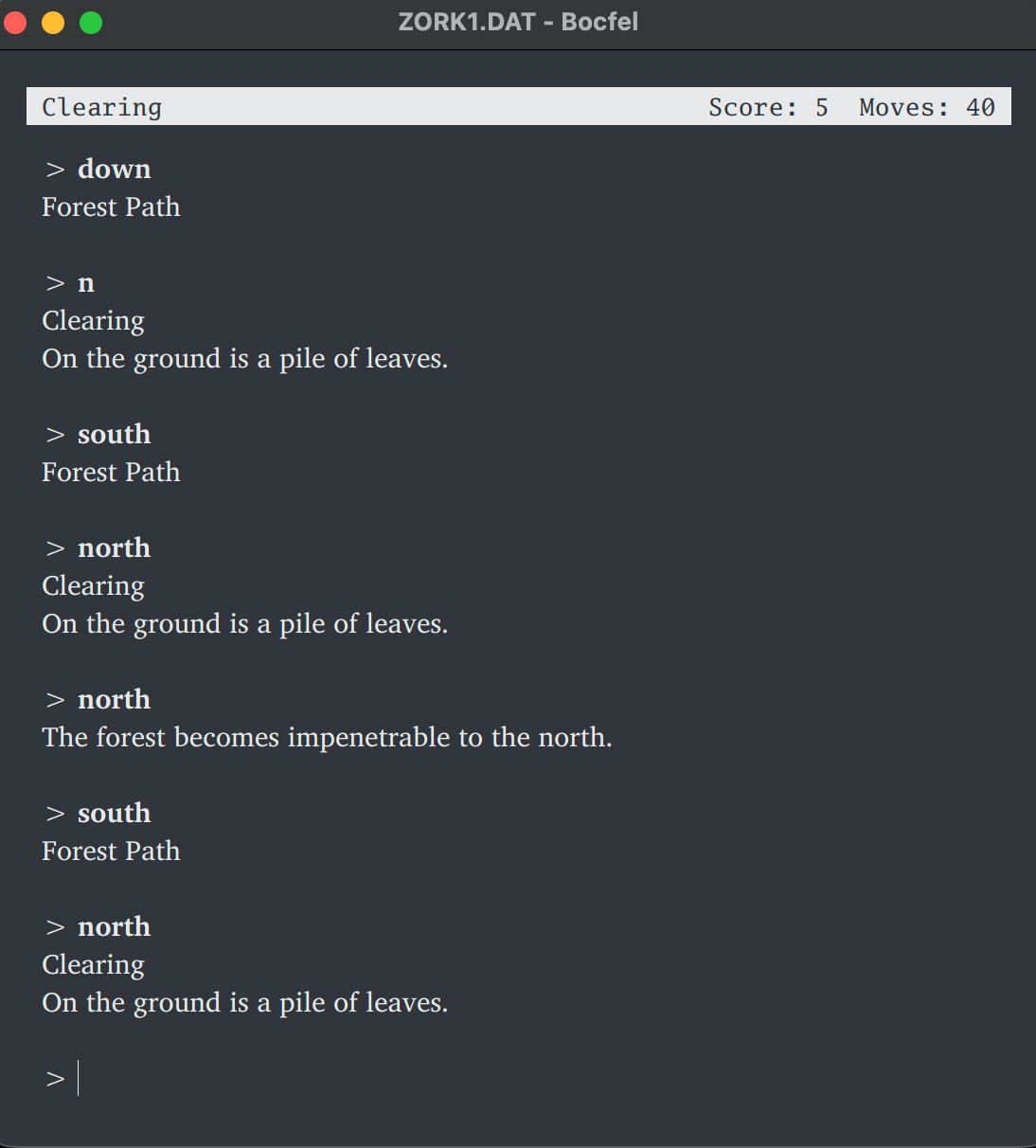

Piece of cake. Just start your application, and have a python script remote control that window typing the contents.

This is a tiny example so GPT-5-mini is a nice start.

Since we are talking about on screen text the starting point can be just OCRing with something like tesseract (so it is faster) and send the things to the llm outputting the response.

First gameplay? Surprisingly fine.

Ok, ok. I know going rogue on that troll was not the smartest thing. But for a first iteration it is not bad. Now, unfortunately it is very hard for the LLM to know that it can resurrect or even restart the game. So let's add some small context.

Experiment 2: Giving more context to the agent

The LLM, at this moment is treating each and every room individually as it saw it afresh. In Zork there is this weird Loud Room that just echoes everything you type. The agent gets crazy and tries to restart the game. It is fun because that is one room where you cannot restart the game. That makes it enter an infinite loop.

A naive solution for this is to just turn the dialog of the game in a conversation with the agent with the agent storing all the messages in the context.

For long sessions the context may rot so let's implement a sliding window. I experimented a bit with the number of messages to keep. I started with 50 or 100. With those numbers the game plays far better. Anyway, there is not enough context to learn from more than one game. You just avoid the last death in the best case scenario.

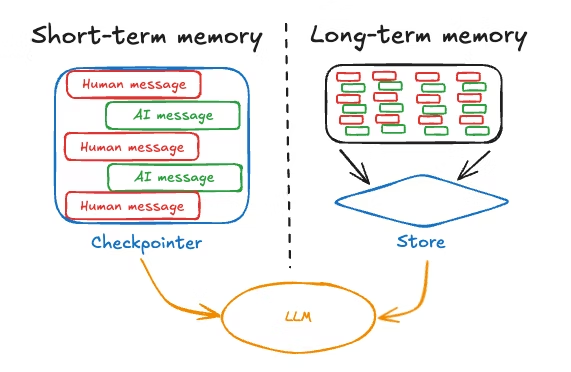

Experiment 3: Giving it long term memory

Right now, the agent learns a bit from history but it would be great if it had the ability to keep things like where objects are and what happens if you try to swing your sword to that troll.

That is the purpose of the long term memory. You distill the content a bit more there to avoid having a lot of pollution and you also keep a short term memory so recent events have some degree of preeminence.

In LangGraph we have the checkpointers that allow us to do this easily.

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, START, END

from langgraph.checkpoint.sqlite import SqliteSaver

from langchain_anthropic import ChatAnthropic

from typing import TypedDict, Annotated

from langgraph.graph.message import add_messages

class State(TypedDict):

messages: Annotated[list, add_messages]

def chatbot(state: State):

llm = ChatAnthropic(model="claude-sonnet-4-20250514")

response = llm.invoke(state["messages"])

return {"messages": [response]}

graph = StateGraph(State)

graph.add_node("chatbot", chatbot)

graph.add_edge(START, "chatbot")

graph.add_edge("chatbot", END)

checkpointer = SqliteSaver.from_conn_string("chatbot_memory.db")

app = graph.compile(checkpointer=checkpointer)

config = {"configurable": {"thread_id": "conversation-X"}}That will persist all the messages states in sqlite. It is not the best way to do it but for now it will suffice.

In our case we will use the game as a thread_id. This way the conversations with the agent won't be mixed between games.

But probably you will be thinking... we are doing the same thing we were doing before, aren't we? And yes, you'd be absolutely right. With this we just implemented short term memory. We need to store some kind of long term memory too.

We will introduce the concept of a game_guide in the state of the agent

class AgentState(TypedDict):

messages: Annotated[List[BaseMessage], operator.add]

last_observation: str

action: str

game_guide: str

steps: intSo the state of the agent now has a game_guide that is updated every X steps. It is like the agent is writing one of those gamefaqs.com guides in text and now that becomes our source of truth.

With this the game gets pretty far. Sometimes it still gets stuck. Especially in areas where the map is special like the forest.

Even if you have the history the model tends to take "impulsive" decisions. If there is a mailbox tends to overspend attention on it taking a look to it and overplaying with it when there is probably nothing else to do.

This is a bit similar to what we do in Claude Code when we compact the history.

Results

I got to 40 out of 350 points.

Impressive IMHO. To be honest I could have got more but I did not want to spend more than 5 bucks in openAI.

Lessons

The prompting is super important. When writing the game guide, it took me some time to notice that it was including information about the state of the current run instead of generic information about the game and that was confusing to subsequent runs.

Observability is a fun thing to do. I keep the plain text file for the memory so I can see what the AI beliefs are at the moment. I am missing a lot of info, though.

Will I continue? Obviously. I really think I can get this to win the game somehow. The cost is a problem now. Probably I will set up something using ollama or some local, even though slower, llm.

The adventure awaits